| Iphri - Efiri - Efri - Ivwri personal shrine figures Ijo and Urhobo peoples, Nigeria |

| Most information and most examples are from: Where Gods and Mortals Meet: continuity and renewal in Urhobo art African Arts, Winter, 2003 by Perkins Foss |

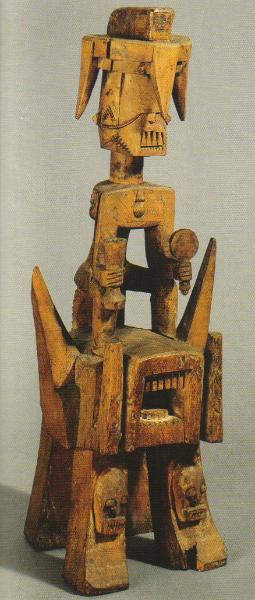

| 5.58a Carved figure (efri) Ijo, Nigeria 19th century? wood 99 x 36 x 42 cm The Trustees of the British Museum, London, 1949.AF.46.188 From the book: Africa - The Art of a Continent |

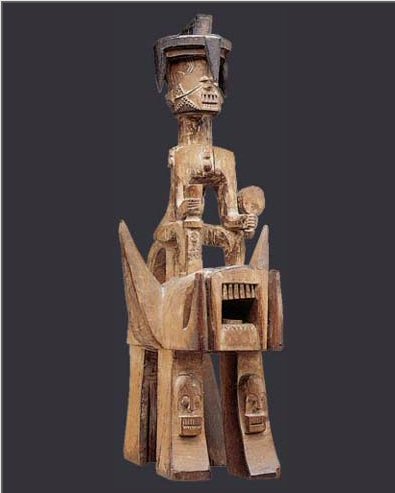

| 5.58b Carved figure (ivwri) Urhobo, Nigeria 19th century (?) wood, pigment 70 x 27 x 26 cm The Trustees of the British Museum, London, 1954.AK23.428 From the book: Africa - The Art of a Continent |

| The powerful Urhobo sculpture (cat. 5.58b) combines human, animal and bird-like qualities in a single complex figure. It stands on four massive legs that support a creature that is little more than a vast, gaping mouth, with great, curving incisors and rows of sharp teeth. The whole of this element arguably constitutes the stomach of the human figure that surmounts it. He, in turn, grasps two lesser figures, surmounted by birds, separately carved, and is him¬self supporting an elephant trampling heads under its feet. All the figures have prominent teeth and facial scarification and that in the centre wears a coral (?) bead at the neck as an indication of wealth and status. Urhobo ivwri (also known as iphri) sculptures are associated with human aggression. The gaping mouth is seen as the focal point. The figures are involved in self-defence from outside attack and the focusing of individual hostility on external enemies. Relatively large sculptures such as this one might be expected to be owned by a whole group, who look to them for protection. Oral histories of individual pieces typically relate the bringing of an ivwri to the foundation of a new settlement. It is normally associated with a particular, successful and aggressive male warrior whose descendants take over the care of the piece. Such works accumulate dangerous powers that are controlled only with difficulty. The possession of such an object is an assertion of status. In previous centuries success was primarily measured in terms of the loss and gain of individuals through the operations of the slave trade, so that ivwri remain conceptually linked to slaving. As part of a larger household shrine, the figure is merely the central element of a much more complex work. In use, such carvings would incorporate a separate triangular screen of slatted cane or wood, attached at the rear of the central figure. Among the Urhobo such an element is known as a 'wing' to empower the object to work at a distance. Fronds of feathery raffia may be hung from the 'wing'. Since this element is much more fragile than the centre sculpture, it has been lost in most museum pieces and indeed is regularly replaced in use. Although usually kept in semi-darkness on a shrine, in at least one case an ivwri is recorded as being placed on the head of a performer who dances with it. The corresponding sculpture from the Ijo (cat. 5.58a) is a similar conception yet is different in so many particulars that the pieces read like the same statement in two different dialects. The Urhobo ivwri rounds out its forms wherever possible, while the Ijo efri squares all its shapes off. The function of the piece is the same as that of the Urhobo and exhibits the same aggression. Nowhere can the stylistic differences between neighbouring peoples be better demonstrated. Although works of this kind are typically interpreted as handling impersonal forces, ritual objects in southern Nigeria frequently externalise parts of the human body — so that movements of the head, hand etc. may have strong moral implications and so make the parts of the body subject to control. The stomach can be seen as a symbol of personal greed and acquisitiveness and this sculpture directs and moderates its excesses. NB Bibliography: Foss, 1975 From the book: Africa - The Art of a Continent |

|

| Statue for male aggression (iphri) Wood Collection of A.C. Lebas |

| Iphri works of art evoke the aggressive energy essential to the ideal Urhobo male personality. In the old days, iphri owners were excellent hunters and, when necessary to defend their families, formidable warriors. They remain well recognized as forceful, dramatic public speakers. An iphri takes the form of a fantastic four-legged beast with multiple layers of teeth. Rising out of its top is an image of the owner of the form. In some cases he seems to be riding the beast; in other cases, the beast seems to be part of his torso. Sometimes he appears with family members flanking him. Iphri ownership is declining today, but at one time a warrior or hunter would have maintained an iphri; even now, a man who has trouble controlling his temper may keep one, as might a man who consistently loses property. A small child who is always tempestuous may be given a tiny iphri to wear around his neck. Certain men who have too much aggression are said to "need iphri." They are often the community's most aggressive individuals, unable to control an overly forceful outlook on life. Iphri, then, have the apparently contradictory function of increasing aggressiveness for those who have too little, and controlling it for those who have too much. An iphri may be carved in many different shapes and its size reflects the social stature of its owner. Prayer to the image, and the actual act of feeding the mouth of the iphri, provide the owner with a more balanced personality. The iphri shrines exhibited in this section demonstrate the extraordinary artistic variety of the iphri genre, and related works from neighboring areas show its strong artistic links to related styles throughout the western Niger Delta. Iphri tore! (Iphri-the-roaster!) Sa iphri! (Iphri-go-on-the-attack!) Edion! (For the good of all!) -- Praise poetry for iphri, by Meriore Arhirhe Edjekota, September 15, 1971 Akanabe is respected for his strength; if he does not stand up to his name, it will be his shame. The time has come for a day to be fixed for battle. My people have made me their leader, and my heart keeps its calm. I hold clubs to my chest on my way to the battlefield. -- Tanure Ojaide Poetry, Performance, and Art: Udje Dance Songs of the Urhobo People, 2003 From: Where Gods and Mortals Meet - Continuity and Renewal in Urhobo Art |

| This photograph depicts a danced performance for a statue for male aggression (iphri) held by the family of Etuke Odjesa, Ogberaka Quarter Edjekota. In the nineteenth century, many Urhobo village groups constantly struggled over land ownership. Iphri were carried at the forefront of attacking. In subsequent generations, these struggles were commemorated in mock battles, with neighboring families assuming the roles of aggressor and defender. (Photograph by Perkins Foss, 1972) "Iphri, works that commemorate aggression, evoke the control and focus of assertive, sometimes bellicose power. Of the three basic types of personal images, the iphri is the most elaborately rendered. It alludes to broad qualities of male leadership, including those of a persuasive public speaker, a group leader, a powerful hunter and warrior. Iphri are also said to protect individuals from losing valuable possessions. These sculptures suggest forces that are quintessential to the Urhobo male personality: aggressive energy, forceful posturing, successful hunting, and powerful oratorical skills. The metaphor extends to all parts of Urhobo male society, and iphri are believed to both increase and, at the same time, control one's aggressive tendencies. While some images are massive and complex forms that exceed three feet in height, in 1971 I saw a four-year old boy--a "difficult child"--wearing a tiny iphri, no more than a half-inch tall, around his neck . Iphri imagery typically includes one or more male figures standing atop or riding a quadruped whose face is dominated by multiple sets of large, threatening teeth. In different parts of Urhoboland, artists render iphri according to distinct substyles." Where Gods and Mortals Meet: continuity and renewal in Urhobo art African Arts, Winter, 2003 by Perkins Foss |

| Additional examples from the exhibition for reference |

|

| Statue for male aggression (efiri) Western Ijo, Nigeria Wood, paint The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Purchase, Matthew T. Mellon Foundation Gift, 1960. (1978.412.404), (cat. 41) This object is an efiri, a term closely cognate to iphri. It is from Patani, a multiethnic trading town on the Forcades branch of the Niger River, south of the Urhobo. The western Ijo peoples in this area readily acknowledge that they developed their own version of iphri to maintain military balance against the Urhobo. |

|

| Statue for male aggression (iphri) Wood, pigment Pace Primitive Gallery, New York |

|

| Statue for male aggression (iphri) Wood, pigment Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Arnold Rogoff |

|

| Statue for male aggression (iphri) Wood, pigment Collection of Henricus and Nina Simonis (frontispiece) This massive figure with huge saberlike teeth personifies the powerful ideals of Urhobo men: physical and moral strength, the ability to speak well in public. In past generations, these statues would have been maintained by great warriors. |

|

| The 3 figures above are from the Collection of Sherry and Terry Sasser - USA Click on photo to see larger version |

|

|

| This piece is in the Geller Collection click above for additional photos |

| A Web Site of Urhobo Historical Society http://urhobowaado.info/exhibit/foss_home.htm With reviews and photos from the exhibition and catalog: WHERE GODS AND MORTALS MEET Continuity and Renewal in Urhobo Art CLICK HERE to go to the website for the exhibition Rand African Art home page Educational Resources page |