|

|

|

|

|

|

New York Times - August 19, 2005

Giving African Art an Example of What It Is Due

By HOLLAND COTTER

A century from now, art historians will shake their heads in disbelief at what universities were teaching circa 2005. How, they will wonder, could

scholars have been so obtuse? Entire courses devoted to that froth called French Impressionism; whole seminars to a prolific pasticheur named

Pablo Picasso, whose chief innovation lay in mining African art for modernist gold. As for the study of African art itself, it was relegated to the margins

of the discipline.

In age, variety and beauty, art from Africa is second to none. Africa had traditions of abstract art, performance art, installation art and conceptual art

centuries before the West ever dreamed up the names. African art stayed vital and culture-altering as the West's avant-garde episode withered away.

So why is African art given such scant attention circa 2005? Why are precious opportunities to study and document it lost for lack of money,

personnel and encouragement? Future historians probably will not have clear answers - cultural blindness is hard to explain. Charitably, they will

assume that universities did what they could with the limited vision they had.

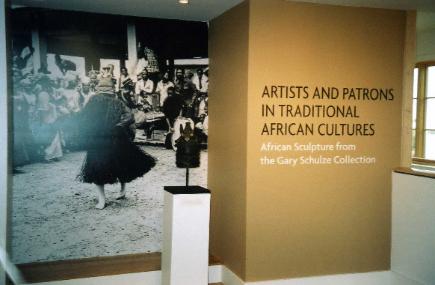

But some universities have a broad vision. The City University of New York is one. Its Queensborough Community College has quietly assembled an

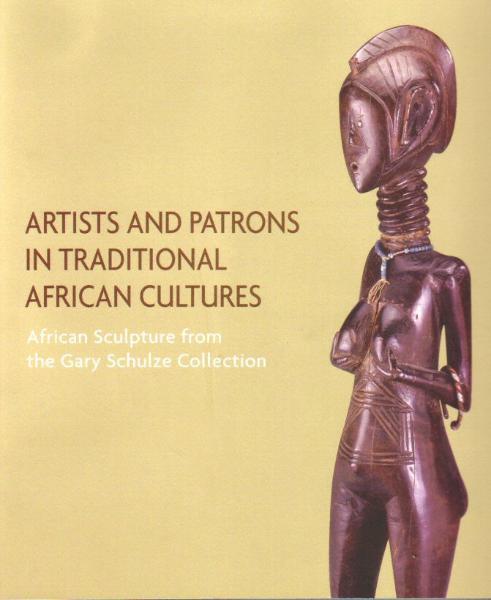

impressive collection of African art. A year ago, the college inaugurated a permanent display of the collection in its campus gallery. This summer the

gallery is presenting nearly 100 privately owned sculptures in an exhibition titled "Artists and Patrons in Traditional African Cultures: African Sculpture

From the Gary Schulze Collection."

Mr. Schulze's interest in African art began when he was in the Peace Corps in Sierra Leone in the early 1960's, and much of the work in the show

comes from there and a few other West Africa countries. Yet because African culture is a fluid, manifold, cross-pollinating phenomenon, the stylistic

range of the objects on view is broad and the chronological span wide, from the second millennium B.C. almost to the present.

Giving shape to such diversity isn't easy. The curator, Donna Page, an adjunct instructor in the department of art and photography at

Queensborough, tackles the job by adopting patronage as a theme and sorting out 60 objects under categories of royal patronage, religious

patronage and what might be called civic patronage. In reality, distinctions are not so neat, but the scheme works here, giving the show and Mr.

Schulze's collection a graspable logic.

The collection, despite unevenness, has pieces of exceptional interest, even in the context of a city with major institutional holdings of African material

at the Metropolitan and Brooklyn Museums. The show begins with one such work, an exquisite wooden figure of a woman carved in the mid-19th

century by a Temne artist in Sierra Leone.

With her crested coiffure, long neck carved in coils, and abdomen lightly marked with beautifying scars, she is a study in orderly patterning. Her lithe

figure and clear face adhere to a feminine ideal of both form and character. The way she touches her breasts, as if in a gesture of offering, speaks of

a generosity of spirit that is the truest meaning of fertility.

Ms. Page notes in the slender exhibition catalog that this sculpture and a similar one in the British Museum are among nearly a dozen thought to have

been carved by the same artist, his or her name unrecorded.

The sweeping assumption that anonymity is a condition natural to African art is wrong. The names of important artists were, in fact, well known in their

day, except to colonial collectors who either didn't understand local languages, or who, as they carried off a sculpture, simply didn't ask, "By the way,

who made this?"

The fact that Mr. Schulze, when in Africa, not only asked the question but spoke with the artist himself gives one of the show's several beautiful,

gleaming Sande Society masks a sense of personal magnetism. The piece was carved by Kondeh Bundu, a Mende artist in Sierra Leone, whom the

collector photographed and interviewed. The interview, recorded in 1962 and included in the catalog, suggests that this "unanonymous" artist well

knew his own worth and his fame.

When Mr. Schulze handed him an ancient stone carving from the collection of the Sierra Leone national museum for an inspection, the artist accepted

the piece as a gift. "Tell the government that your friend, Kondeh, the carver, wanted it. Tell the prime minister that Kondeh Bundu of Waiama wants

to keep it."

In fact, Mr. Schulze himself collected a good amount of similar archaeological material, and Ms. Page has installed a sampling on the gallery's second

floor. The oldest pieces are sleek terracotta heads and figures first dug up by tin miners working near the town of Nok in Nigeria in the 1920's. Dated

between 500 B.C. and A.D. 500, they put to rest any lingering myth that African art is without a deep history.

Then there are the small, expressive, large-eyed stone figures that farmers in Sierra Leone came across when clearing fields. Tentatively dated from

the 15th to 17th centuries, they are attributed to a group of related peoples referred to collectively as the Sape Confederation. The confederation is

thought to have extended over parts of present-day Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea, a reminder that African national boundaries as they exist now

were largely created by Europeans to divide up their spoils.

In the end, the most reliable, organic indicators of African cultural realities, which often represent its political realities, are to be found in its

boundary-crossing art. This fact automatically lifts the study of African art history from the status of academic luxury item - a cosmetic extra tacked on

to keep those multiculturalists quiet - to intellectual and existential necessity. Without it, the label "Department of Art History" is a sham.

This necessity makes both the Queensborough show and its fine and growing permanent African display - organized by the gallery's curator, Leonard

Kahan, and its director, Faustino Quintanilla - important events as well as aesthetic pleasures. That permanent display will be in place for years to

come. With luck, other university galleries around the country will emulate it, and their numbers will grow, just as the global influence of Africa itself

continues to increase.

Maybe, after all, art historians in 2105 will be shaking their heads in admiration at what our century accomplished. One thing is certain: many of those

scholars of the future will be African.

|

|

|

|

|