| KUBA |

| A Kuba Mask Bonnie E. Weston |

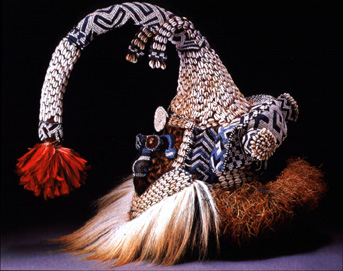

| The Kuba live in the Lower Kasai region of central Zaire in a rich environment of dense forest and savanna. Organized into a federation of chiefdoms, the almost 200,000 Kuba are a diverse group of over eighteen different peoples unified under the Bushong king. They share a single economy and, to varying degrees, common cultural and historical traditions. Agriculture is the main occupation, supplemented by hunting, fishing, and trading. The name "Kuba" comes from the Luba people to the southeast. The Kuba call themselves "the children of Woot"— after their founding ancestor (Vansina 1964:6;1078:4). Praised as "God on Earth," the king, nyim, is a divine ruler who controls fertility and communicates with the creator, Mboom. The royal court at Nsheng is a hierarchical complex of councils and titled officials who advise the king and balance his power. Outlying Kuba chiefdoms are largely autonomous, organized on models analogous to those of the capital but on a lesser scale (Vansina 1964:98-99; 1978:216). Kuba society parallels governmental organization in that it is stratified. Yet the Kuba people prize hard work and achievement, and while position of birth may secure advantage, it is not binding (Vansina 1964:188;1968:13,15). Kuba religion, however, is not highly organized. The creator, Mfcoom, is recognized but is not formally worshiped. More considera¬tion is given to Woot, who led the Kuba migration "up river" and established matrilineal descent, male initiation, and kingship. Local nature spirits, tended by priests and priestesses, are actively involved in people's lives, notably in matters of fertility, health, and hunting. The Kuba have no ancestor cult but do believe in reincarnation (Vansina 1964:9-10). Kuba arts primarily address status, prestige, and the court; they are manifestations of social and political hierarchy. Rank and wealth are expressed in extensive displays of regalia: jewelry, rich garments of embroidered raffia cloth, ceremonial knives, swords, drums, and elaborated utilitarian items. Valuable imported cowrie shells and beads emblellish garments, furniture, baskets, and masks. The outstanding Kuba style diagnostic is geometric patterning used to embellish the surfaces of many objects. These designs are woven into raffia textiles and mats, plaited in walls, executed in shell and bead decoration, and incised on bowls, cups, boxes, pipes, staffs, and other forms including masks. All art forms and designs are laden with symbolic and iconographic meaning, and the same is true of the rich Kuba masquerades. Masking was first introduced by a woman who carved a face on a calabash, the original model for initiation masks. The invention was taken over by men, incorporated into initiation, and remains a male privilege. Once Bushong boys move into the nkan initiation shelter, they can wear masks and make excursions into the village frightening women and small children. More powerful masks are worn by initiation officials. The masked Kuba dancer is, in every instance, a spirit manifestation (Torday 1910:250; Vansina 1955:140). Three royal mask types exist: the tailored Mwaash aMbooy, representing Woot and the king; the wooden face mask, Ngady Mwaash aMbooy, the incestuous sister-wife of Woot; and the wooden helmet mask, Bwoom ,the commoner. These characters appear in a variety of contexts including public ceremonies, rites involving the king, and initiations. Although their dances are generally solo, together the three royal masks reenact Kuba myths of origin (Cornet 1982:254,256; Roy 1979:170). Bwoom is a wooden helmet mask elucidated by varied oral traditions. The Kuba feel that one " 'understands' the why of something if one knows how it 'began'; something is known if it is explained" (Vansina 1978:15). Thus Bwoom is the spirit first seen by nkan initiates; he is a hydrocephalic prince, a commoner, a pygmy, or one who opposes the king's authority. Two traditions trace Bwoom's origin to the reign of King Miko mi-Mbul, who had gone mad after killing the children of his precedessor. Although he finally became sane, Miko would lapse into madness each time he wore Mwaash aMbooy, the most important royal mask and until then the only one worn by the king himself. A pygmy offered the king Bwoom as an alternative. Suffering no ill effects with the new mask, Miko accepted it. A less dramatic version is that Miko, known as a great dancer, was simply seduced by the pygmy's creation and adopted it despite its humble character. In both cases the King is credited with improvements to the mask that justify its inclusion in the royal repertoire (Cornet 1982:269). As inconsistent as they may seem, each account expresses an aspect of the mask or its character. The identification of Bwoom as a pygmy or a hydrocephalic man is often cited to explain the mask's enlarged forehead and broad nose. Bwoom appears in initiation and is always considered a spirit. The lowly origin of the character is reflected in its description: "a person of low standing scarcely worthy of being embodied by the king" (Cornet 1975: 89) and conversely in its defiant performance opposite the regal Mwaash aMbooy. The two may act out a competition for the affections of the one female in the royal mask trio, Ngady mwaash aMbooy (Cornet 1982:255). Mwaash aM-booy's dance is calm and stately, while Bwoom acts with pride and aggression (Cornet 1982:255). The masks are easily differentiated by material, for Bwoom is carved from a single piece of wood and Mwaash aMbooy is made from cloth and raffia textiles. Bwoom appears on the nkan "initiation fence" of the Bushong (Vansina 1955:150-151) and in other initiation contexts. Little is known of this mask (or indeed most Kuba arts) outside of the royal Nsheng tradition. A royal mask, Bwoom is sometimes worn by the king. Yet unlike Mwaash aMbooy, Bwoom does not appear at funerals, and it is never interred with the king or other dignitaries (Cornet 1982:270). The costume is similar to that of Mwaash aMbooy: heavy with profuse layers of raffia-cloth, bead and cowrie decoration, leopard skins, anklets, armlets, and fresh leaves. Eagle feathers or other prestigious media are added to the crown of the head when the mask is danced. Despite regional variations, the Bwoom mask conforms to a distinct type. All styles feature strongly rendered proportions dominated by an enlarged brow, broad nose, and usually naturalistic ears. Typical features include the metal work on the forehead, cheeks, and mouth, bands of beads that embellish the face, and an expanse of beadwork at the temples and back of the head. Plate 8 has these plus patterned raffia-cloth covering the top of the head, with a fringe of hair. The blue beads set into the white band at the temples imitate ethnic tattoo patterns (Cornet 1982:266), and the design at the back of the head is one associated with royalty. |

| Mukenga / Mukyeem A non-royal variant of the Mwaash aMbooy type mask is the Mukenga mask, representing an elephant, is characterized by a beaded trunk and two small tusks protruding from the base of the trunk. As in other African kingdoms, such as the Asante and those of the Cameroon grassfields, elephants are associated with royal power. According to the Kuba proverb, "an animal, even if it is large, does not surpass the elephant. A man, even if he has authority, does not surpass the king (Binkley 1992: 277). The small beaded tusks flanking the trunk symbolize wealth and fertility (Binkley 1992: 288). Mukenga masqueraders perform at the funeral ceremonies of high-status Kuba titleholders. |

| THE OBJECTS BELOW ARE NOT IN MY COLLECTION, THEY ARE FOR REFERENCE PURPOSES ONLY |

| From: http://sirismm.si.edu/eepa/eep/eepa_04035.jpg There are a LOT of great photos in the Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives |

| Sotheby's piece Property from a New York Private Collection A FINE KUBA MASK LOCATION ESTIMATE AUCTION DATE New York 7,000—10,000 USD Session 1 15 Nov 02 10:15 AM Lot Sold. Hammer Price with Buyer's Premium: 10,755 USD height 21 1/2in. 54.6cm mukyeem, of helmet-like form and large proportions a raffia attachment at the base, composed of a flat metal facial plane pierced through for attachment of the expressive beaded facial features, and wearing an elaborate headdress composed of blue, white, black, pink and red beads and cowrie shell, a conical projection at the crown in the form of an arching elephant trunk framed by two tusks. Provenance: J. J. Klejman, New York Sotheby's, New York, November 15, 1988, lot 124 |

| Elephant Mukenga Mask Culture: Kuba Cowrie Shells, Beads, Raffia, Fur, Cloth http://www.ohiou.edu/~afrart/GalleryPageD.html |

| Mask (mukyeem), 19th–20th century Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kuba peoples Wood, beads, fiber, hair, cowrie shells, and cloth; H. 18 in. (45.7 cm) Private collection Source - http://www.metmuseum.org/special/Genesis/10.L.htm |

| http://www.uic.edu/depts/ahaa/classes/ah111/kuba.jpg |

| Mukenga Mask Kuba Culture, Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire) 1800s-1900s Wood, animal fur, raffia cloth, cowrie shells, glass beads, string 19 1/2 inches high Virginia Museum of Fine Arts Purchase, The Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund, 87.82 |

| C. Pollzzie Collection Acquired from the McDonald-Levy Collection Height: 33 in. (84cm) Width: 20 in. (51cm) Depth: 18 in. (46cm) |